Yoshida Hiroshi : Print-maker : Part One

THE ART OF WOOD-BLOCK PRINTING IN COLORS - chromo-xylography, to give it the somewhat uninviting technical name - is one of the few cultural media of Japan not owed in its main lines to a Chinese original. The printing of designs, or of written inscriptions, from wooden blocks did, indeed, come from China, perhaps a thousand years ago; but that utilitarian, monochrome printing process developed only in Japan into the production of those many-colored works of art - works which, from their usual depiction of scenes of 'the passing world', we know as the 'ukiyo-e' art - which ornamented the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

This purely Japanese art of the Ukiyo-e School, then, burst upon the Western world a hundred years ago with the splendor and the charm of a genre completely unknown and utterly new; and the inspiration and stimulus drawn from it by Western artists from Whistler to Brangwyn is a matter of common knowledge. But before ever the world had made its discovery of Ukiyo-e, that art had fallen into its decadence. By the time of the opening of Japan, the current productions of color-prints could no longer be dignified by the name of art; and by late Meiji times - say, the turn of the twentieth century - it was clear that the art was dead. Not only dead, but, by pronouncement of all the critics, never to be reborn. "To-day", wrote Ficke in 1915, "the old art of the colour-print is completely dead. ... It is idle to hope that real vitality will ever return to animate this lost art". Print-making had, during the lifetimes of Hokusai and Hiroshige, "rapidly declined to extinction upon the death of the latter in 1858", says another; "even at the present day no Western pictorial art can approach the artistic excellence, in composition, line, and colour, of these prints produced a hundred to a hundred and fifty years ago; and it is to be regretted, from an artistic point of view, that the art has been so completely lost". And another: "If we should ask, in conclusion, whether it is conceivable that the Japanese will ever again attain a characteristic and important art on the basis of the ancient traditions, the answer, it would seem, must be in the negative. ... A new Japanese art would of necessity have to be founded on an entirely new basis, which could certainly not be that of European art".

The critics were unduly pessimistic. Just in early Taisho when the first of the passages above quoted was being penned, the color-print art was being reborn, to develop rapidly to the thriving condition to which it has attained in our day. What was reborn was not, of course, the art of Tokugawa days, not Ukiyo-e - that in which life has once become extinct cannot be resuscitated - but a modern art, which on the technical and artistic foundations of Ukiyo-e creates something of our own time. In this renascence are many honored names. Hashiguchi Goyo, from whose maiden work of 1915 we may date the modern art of wood-block prints, is dead these many years; Watanabe Shozaburo, merchant of art extraordinary who gave the impetus and supplied the backing, is with us yet, as are Kawase Hasui and Ito Shinsui, pioneer artists of the revival. But now we have lost, in Yoshida Hiroshi, who died a few weeks ago, another of those pioneers, of them all the best known to the West as artist and philosopher of the art of the color-print.

MR YOSHIDA DID NOT APPEAR ON THE COLOR-PRINT SCENE among the very earliest. He was already a painter in oils with a reputation not only in Japan, but European and American as well when, at the age of forty-four, he produced his first wood-block print. That was in 1921. From that time forward, for the rest of his life the major part of his thought and creative power was devoted to color-prints, with the result that at his death he leaves a body of work in that medium which for variety, artistic integrity and pure pictorial beauty stands in the very front rank of art.

Yoshida Hiroshi was born in the city of Kurume, Fukuoka Prefecture (the old Chikugo Province), in Kyushu, on 19 September 1876. He early manifested an aptitude for art, which was fostered by his adoptive father, himself a teacher of painting in the foreign style in the public schools. The talent was so marked that at his age of nineteen the boy was sent to Kyoto to continue his studies under the well-known teacher Tamura Soryu, and in two years of work there Yoshida became an accomplished painter in oils. Three years of advanced study in Tokyo with Koyama Shotaro, one of the three or four most famous foreign-style painters of his time, completed the training.

Now a finished artist so far as Japan could make him one, Mr Yoshida set out to study his art in its original home in the West. In 1899 and 1900 he was in America and Europe - a year in each - studying, exhibiting, making and selling pictures, forming friendships. In the United States he visited galleries and showed his own works in Detroit, Boston, Washington, Providence and elsewhere. In Detroit there were two fortunate happenings: first, he took prizes in an exhibition sufficient to refund to his relatives the loans which they had raised to enable him to travel; second, he renewed the acquaintance (begun in Japan) of Charles L. Freer, who was just then retiring from business to devote his entire time to those services to the cause of Oriental art in America which are too well known to require mention, and who bought some paintings and gave the artist useful introductions. In Europe as well, Mr. Yoshida had successes, taking a prize at Paris and exhibiting also in Italy, Germany and London. The main object, however, was study; and he haunted the museums and galleries, analyzing the works of the old masters for ways of improving his own art, and always sketching and painting.

Returning to Japan, Mr Yoshida stayed long enough to found (in 1902) the Taiheiyo Gakai - the Pacific Art Association, with which the rest of his life was closely bound up - but he soon heard again the call to travel (his ears were never to become closed to it), and in 1904 set out to see the St Louis Exposition. In America he again exhibited - at the Exposition, at Boston, and elsewhere - and spent, this time, almost two years in study and at work. From America he continued to Europe, where there was more exhibiting, studying and painting among scenes old and new - this voyage was extended to Switzerland and Spain, and to North Africa, and thence home to Japan via Egypt and Port Said. On this trip Mr Yoshida was accompanied by his wife, Yoshida Fujio, herself then already and still today a painter of much distinction in water-color and oils; from the three years' stay came a large product of paintings by both of them - scenes from Luxor, the Alhambra, the Alps, Mount Ranier and the Grand Canyon - which may now be seen, with their pictures of Japan, in the museums and private collections of the world. Out of it came also a book in which Yoshida extolled a corner of Europe which exercised a particular fascination over him as scholar and as artist: Makyuden kembunki - shasei ryoko (The Magic Palace: Personal Experiences on a Sketching-Tour), a rhapsody on the architecture, the legends and the enchantment of the Alhambra.

After this tour abroad Mr Yoshida was for some years relatively fixed - 'relatively', because he remained in Japan. First the need of expressing in pictures the ideas filling him, and his growing reputation, with its concomitant teaching, serving as juror for national exhibitions, and the rest; then World War I, making travel difficult and dangerous, held him at home. But the Wanderlust was merely localized, not eradicated; and during this period he began exploring the confines of his own Japan. Now commenced the annual trips, never omitted until his years became too many, for mountaineering among the Japan Alps; month-long tours around the Inland Sea produced their quota of pictures; from Hokkaido to Ryukyu the artist roamed Japan, seeing and painting its beauties.

At about the time of the end of the War - around 1919 - Mr Yoshida became interested in wood-block prints, and he made a few of them which were published by the house of Watanabe in 1921 and 1922. The blocks, and substantially the entire editions of these prints (all except the few copies which had been sent to America or elsewhere out of Tokyo), were destroyed in the Great Earthquake disaster of 1 September 1923 - making these among the great rarities of print-collecting; but Mr Yoshida had become possessed by a new fervor, one which never left him. With the end of the War travel had again become practicable, and he and Mrs. Yoshida set out once more, in December 1923, for another two years' sojourn in America, Europe and Africa, where as usual they exhibited, sketched and did sight-seeing - and, as usual, sold the paintings of brother-artists as well as their own. After returning to Japan Mr Yoshida began with a renewed enthusiasm to work at print-making, and into this medium for the rest of his life he put his greatest efforts and his most loving care, poured the results of a lifetime's travel and study, and all the beauty which he had stored up in memory or thereafter found. In 1929 - 1930 he spent several months in India and Southeast Asia - a voyage which produced a notable portfolio of prints - and in 1936 he visited China, Manchuria and Korea; but for the most part the work of the two decades past has been devoted to the recording of the Japanese scene.

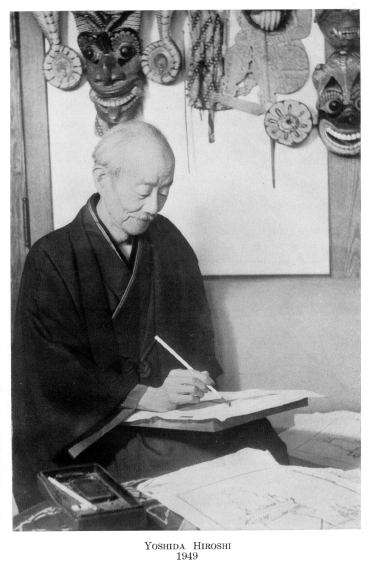

Once again war came, circumscribing the lives of artists beyond those of most people. After 1941 Mr Yoshida could not travel, except to China (he made three war-time trips, which resulted in picture-postcards for the cheering up of soldiers at the front); and he made no new prints, except for a few already designed and cut before 1941, but finally printed only after 1945 (two remain yet unprinted). The recent years were devoted to making new impressions from the old blocks, to brief sketching-trips (no longer to such far or such high places as of old), and to relaxation among the remarkable family of artists of whom he was progenitor. In October 1949, while on a sketching-trip at Nagaoka, in Izu, he fell ill; he was brought home to Tokyo, and seemed convalescent; but on 5 April of this year, while still in the prime of his powers and his enjoyment of life and of work, he died at his home in Shimo-ochiai. His tomb is in the grounds of the Ryuun-in, in Koishikawa, Tokyo.

MR YOSHIDA'S DECISION TO DEVOTE HIMSELF TO THE making of color-prints was the outcome of a conjunction, characteristic in him, of intellectual and artistic processes. He came first to consider the medium as a result of perceiving the high esteem in which it - that is,Ukiyo-e - was held by the art-lovers of the West. It commended itself to him moreover as a medium suitable for a Japanese artist because all the materials needed for the production of prints were of Japanese origin and were to be had in Japan; and the techniques of the art were of course purely native. He, groping like so many artists of modern times for a national form of expression, here found "an art which may be truly said to be Japanese", "something which is purely national in the highest and best sense".

He therefore commenced to study the legacies of Ukiyo-e. He was very soon impressed with the fact that - as our critics quoted above had said - the old art not only was dead, but would if revived be the merest anachronism. 'We cannot help observing', he said

... that those artists who have followed the style of wood-block printing developed during the Edo Period have more and more gradually, even from before and through the Meiji and Taisho Eras, fallen short of the achievements of that period. No one can deny that there has been a continued copying but with the imitations rather poor comparatively. A renaissance is needed by which the creative art of the present period may bring new vitality and power to the wood-block colour print. Imitation must yield to the new creative power grafted on to the foundations so well laid during the Edo Period.

...

The outstanding need of the art of wood-block printing today is that, upon the foundation so brilliantly laid by the masters of the Edo Period, there be built something distinctive of the present age. At least there should be an ingrafting of modern creative genius upon that foundation and not the rather halfhearted efforts to imitate that which is foreign, as is seemingly being essayed by some modern artists.

And again:

If an artist likes to follow the style of Hiroshige, he may do so, though his choice does not interest me, for the subjects treated and the manner employed are no longer closely connected with our present life and activity. We no longer have to walk along the Tokaido line, wear sandals, and carry mushroom umbrellas, as pictured in the prints by Hiroshige. But if an artist should be interested in making such a picture, he may do so so far as the subjects are concerned, but he should not attempt to treat them in the spirit of the Edo Period, which has already passed.

The color-print process is, as compared with those of the other graphic arts, one of great complexity. The production of a print calls upon three different skills: that of the painter who makes the original drawing; that of the carver of the blocks; and that of the printer who takes the impressions by hand. As soon as Mr Yoshida had begun to study the processes of print-making he keenly felt, as many students of the art have done before and after him, the unsatisfactory character of the product which results if the artist merely paints a picture, handing it to an independent craftsman to be used in cutting the blocks and in turn passed on to another independent artisan to be printed. The resultant print, however beautiful as a work of art, however technically admirable, will be, not the work of the artist as projected by him into a color print, but only his idea as interpreted by others:

"It is evident that such a process could not but entail a great loss in that, for the production of the finest woodblock colour print, the creative art and vision of the artist is needed not only in the sketch but in the cutting and printing as well. Only in this way can continuity be assured and the vitality and power of the artist shown in full in the final result".

Feeling thus, Mr Yoshida constantly insisted upon the necessity of the artist's being able to do every part of the work, from the wrapping of the baren (the printing-pad of bamboo with which the print is rubbed on the block to force the paint into it) to the cutting of the blocks and the printing of the sheets. To the end of his career he kept his hand in by cutting or printing from time to time - for example, the key-block of Rapids [113] , one of his favorite prints, he himself carved, spending more than a week continuously at it, to his considerable physical discomfort (toothache) afterward. One man of course could not physically perform all the work of making sketches, cutting blocks, and printing fifty to a hundred copies of every print (some requiring up to a hundred impressions each); but the cutting of the blocks and the printing of his works were from 1925 onward always done under Mr Yoshida's direct supervision, by artisans permanently employed by him - he likened himself to a conductor, playing on his orchestra of workmen. The result is a greater consistency throughout the entire body of his work, and a more marked individuality in his prints, than in the case of perhaps any other modern color-print artist. Only after the print had been produced under his eye, then inspected minutely by him for any flaw in paper, registration or color (the slightest flaw resulting in rejection), was it ready to receive his signature in pencil and the marginal stamp 'jizuri', 'self-printed', which was his warranty that the print represented his work.

Mr Yoshida was, moreover, an inveterate experimenter. He was forever experimenting with different papers, or with printing on silk instead of on paper; he tried making blocks of various woods other than the standard cherry, and even using zinc-plates for the key-blocks of intricately-detailed prints; he cut blocks in unheard-of large sizes, he made a series of postcard-size prints; he manufactured, tested out, combined pigments, he made and tried the results of barer& of different materials. Print-making is a complicated task which invites failures; but from his failures in cutting or printing Yoshida was always alert to learn new techniques to be put to use at some appropriate occasion. This venturesomeness of spirit led him into experiments with the other arts as well. In his house one can see, not only his oils and prints and watercolors, but mosaic floors laid and ornamental tables made by him; garden-sculptures which he carved of marble, and Mrs Yoshida's head, modelled in plaster; pictures burnt on cork and other jeux d'esprit of art; wooden grills and wall-panels carved with Indian arabesques or tropical fish, and windows of stained glass (wasn't it Ficke who remarked that stained-glass work resembles color-prints in its requirements of firm outlines, management of color-masses and suppression of unessential detail?) created to his designs.

One of the most interesting of the experiments in print-making was that with oversize blocks. The standard size for prints is mino, formed by cutting in half a sheet of the hosho paper used for them. Of the two hundred fifty-seven prints which constitute Yoshida's life's work in this medium, two hundred are of mino size (printing to approximately 24 x 38 centimeters, or 9 1/2 x 15 inches); twenty-nine are the full hosho size; twenty are of various sizes smaller than mino; and eight are larger than hosho. These large prints, ranging up to 55 x 84 centimeters, are unique in the color-print art, and must be regarded as one of its supreme accomplishments, technically and artistically.

It might seem, offhand, that the production of these large prints would involve no mechanical difficulties other than those inherent in print-making generally - or greater, at all events, only in arithmetical proportion to the sizes. Mr Yoshida's experience proved it to be entirely otherwise. The detailed account which he has given of his troubles with this medium need not be repeated here; a summary will suggest the extent of the ultimate achievement. The first problem was the finding of blocks and paper of the requisite size; it was in fact by chancing onto such blocks in 1926 that Mr Yoshida had got the idea of creating the large prints, but the paper was still a difficulty. Of the two papers used in the making of a print - the minogami for printing from the outline-block the kyogo (the impressions from which the color-blocks are cut), and the hosho for the prints themselves - neither was made in so large a size, and the substitutes which the artist was compelled to use brought new complications with them. When all the blocks had been cut for the first of the large prints and the printing was ready to commence, it was found that the kyogo had shrunk, making the color-blocks too small to fill their appropriate areas of the print. Everything else failing, the artist was compelled to print them by gradations, slipping the paper by stages on the block in such a way as to counteract the shrinkage - in itself a tour de force to be appreciated only after minute scrutiny of the prints in the vain effort to detect any evidence of the improvisation.

The printing of these huge blocks presented another grave difficulty. The blocks and the paper for printing from them were too unwieldy for one printer to manage; and in the first year a pair of printers worked simultaneously on each print. But in the next year the blocks were still larger.

When a large block was placed in position for printing . . ., the printers were appalled. It requires a great deal of strength in printing, yet strength alone is not sufficient; even a champion wrestler may not be able to print such large blocks. It requires a knack. I found that an able printer could not take more than five impressions at a time. If he were allowed to recuperate, the intervals would spoil the paper [which, printed while damp, must not be permitted to dry out]: therefore the work must be carried on continuously. So I engaged two more printers for the work, shifting them after every five sheets.

Despite these and other troubles, the artist succeeded in producing in three years of work a number of prints which - although, as he remarked, "economically the result was not commensurate with the trouble involved" - take place by reason not only of their intrinsic worth but of their rarity as well (the editions of these prints were mostly very small, in the case of the largest sizes only forty-five or fifty copies) as the cynosure of any collector's portfolio of wood-block prints. His own favorite among them, Rapids, a close-up view of the tumbling, foaming waters of a mountain-stream, is a striking 'Symphony in Green'. With Rapids, the largest of the prints is A Sea of Cloud at Ho-zan [112], a choice example in a field where Yoshida's mastery is acknowledged.

The painstaking over the details of the production of the prints was matched by the meticulous attention to the drawings for them. First, the planning of the sketching-trips: the India voyage was preceded by methodical months of study of guide-books, almanacs, and reproductions of monuments of art, with the departure-date finally settled with the aim of assuring that the artist and his son Toshi, who accompanied him, should meet the full moon of December at Agra and good weather for the sunrise on Kanchinjanga. (The elder artist managed on shipboard en route to close a door on the fingers of his sketching-hand, and the younger to contract dengue fever at Penang; but the first healed in good season, and the second resulted only in an acceleration of the itinerary which enabled them to keep their rendezvous with moon and sun.) Then, looking into Yoshida's sketch-books, one marvels at the patience there evidenced. The original drawing for his large print of Chicks [125], for example, occupied him for a full summer. In the studio he erected a cage, and there he spent those months looking at and sketching chicks, from pip to pot (need it be added that it was never the Yoshida pot into which those birds, each with its own name and its own personality so familiar, went to be eaten?). One seems to detect that it was with a trace of impatience that his family endured that summer of 1928 and its unending procession of chickens hatched, sketched, matured and given to friends, to be succeeded by another generation and yet another. In the sketch-books of those days are to be found scores, hundreds, of sketches of 'Bunchan' and 'Daisuke' and 'Masako' and the rest of the chicks, at every age, in every posture, engaging in every pursuit known to the genus Gallus. Another sketch-book will contain an elaborated drawing of, perhaps, Kagurazakadori [82], complete in every detail but wanting the figures in the foreground, a dozen essays for which will be found elsewhere. Or a third, Hodaka-yama [99] or another peak of the Japan Alps, appearing in its finished state down to the careful notations (in English) of the colors to be used - but without the clouds, one of Yoshida's chief specialties; those must be selected from among half-a-dozen fully-worked-out sketches of cloud-effects only, elsewhere in the volume.

THE EARLIEST YOSHIDA PRINTS ARE TODAY, AS HAS BEEN mentioned, so rare that they may be considered unobtainable. Of the remaining works, all - except four made for special purposes [101, 208, 209, 236] - can be had with the exercise of diligence and some patience. The pre-earthquake productions offer some points of interest. Firstly, all of them - there were seven - were of double (full hosho) size. Secondly, their general appearance and spirit differ markedly from the artist's later work - the result, doubtless, of their having been cut and printed by craftsmen not under his direction. Thirdly, three of these prints were variants, printed from the same blocks but in differing colors and moods, of the same picture, a sailing-boat in morning mist, in full day and in evening glow.

All of the pre-earthquake prints were substantially recreated in later years. The Sailing-Boat series was taken up and elaborated into a set of six variants which constitute one of the most striking examples of Yoshida's art [53 - 58]. These betsuzuri - special prints by way of color-variants - had been little used before that time for more than novelty-effect. Yoshida utilized the device to create a distinctive type of work of art, in which the several moods and atmospheres should, by their contrast, mutually emphasize their interest. In addition to the Sailing-Boat series - where, using the identical blocks but for minor omissions or additions of impressions, he has given us six prints, each of entirely different feeling from the rest - he made several pairs or series of betsuzuri; among them those of The Matterhorn by day and at night [17 - 18], The Ruins of Athens [20 - 21], Himeji Castle [43-44], At Itoigawa [129 - 130] (a specially charming pair), and Kanchinjanga by morning light, at noon and in afternoon [150 - 152]. This last triptych is one of Yoshida's masterpieces: as we stand on Tiger Hill a thousand feet above Darjeeling, our eyes rise from the town below to the most magnificent. panorama of mountains which the world affords, a great sweep of valley and snow-fields culminating in the towering height of Kanchinjanga.

By morning the eastern faces of the range are roseate, the rest in deep shadow; afternoon-glow tints the western slopes saffron; and at high noon the 'brave figure' of the peak stands out in the dazzling white of its perpetual snow. The more one studies the prints, the more one wonders at the artistry which with the same blocks could produce this stunning range of effects.

After his return from America in 1925, Mr Yoshida set to work again, and produced prints bearing the date of every year but one from 1925 to 1941 - in 1934, when their home and establishment were being moved from Nakazato to the new house in Shimo-ochiai, there was no studio ready for use, hence no color-prints of that year. Nineteen twenty-six was annus mirabilis: of that year's date we have forty-two prints, including many of the finest ones; 1928 produced thirty-six and 1931 twenty-one - part of the fruits of the Indian trip. Yoshida's work in the medium of color-prints ranged the whole of the Northern hemisphere; and among the prints from his hand are works representative of almost every genre familiar to the art: mountains, rivers and seas; temples and ancient ruins; fauna and flora, gardens, street-scenes and 'the passing world'. In the department of figures only did he show little interest. His portraits and figure-work in oils are sufficient to dispel any doubt whether his talents extended to portrayal of the human form; the fact is that the people in his prints are lay-figures, needed for the composition - he wasn't interested in them as people or countenances. One of his most polished prints, indeed, is that of A Child [97] - a portrait of his second son, Hodaka - which, printed from the unusually small number of ten blocks, received a total of eighty impressions, sixty of them on the face alone.